Chris Jackson spoke to Josh ahead of the Wellington premiere of “Static VI” — the latest and final instalment of his iconic series.

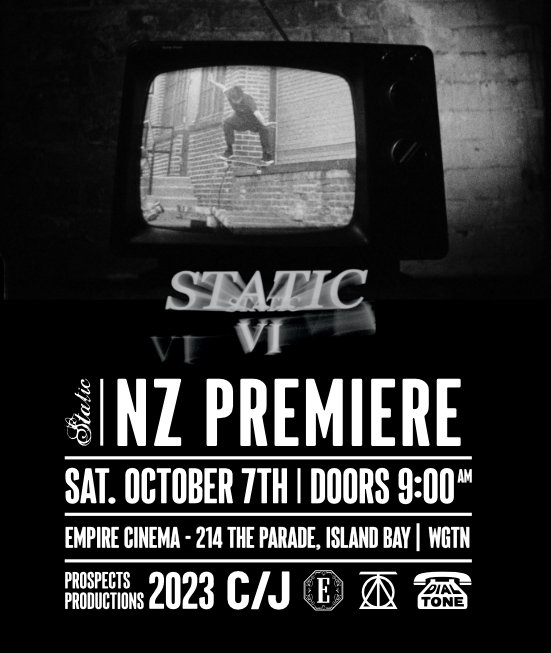

Do you want free tickets to the Wellington cinema premiere? Tickets to the Saturday, October 7 screening at Empire Cinema, Island Bay, are limited.

Another self-funded video with tours and premieres and all the stress that comes with that. It seems like a lot of work. Why put yourself through it?

I have a full-time job running Theories of Atlantis. It’s more than a full-time job. It’s impossibly full-time. And it’s not like I’m not doing stuff. I do tons of video projects for Theories and Hopps.

All that stuff is fulfilling. But my identity has gotten wrapped up in Static. It’s been nine years since the last one. And I have a sense of measuring my self-worth by that output. It feels like I’m letting myself down or not contributing to skateboarding when I’m not doing it.

The other aspect is that I’m constantly seeing and hearing things that inspire me. I have this huge playlist of songs saved for future skate videos. But there are certain songs that I don’t even make visible on Spotify because I’m so worried that, somehow, somebody’s going to find it.

There’s music I save for skate videos. And then there are certain songs that are so haunting and unique that I save them. This stuff starts building up and gets caught in these personal filters of music, visuals, and skaters.

So I keep saving all this stuff for Static.

Music can make or break a skate video. You can kill a video part, or you can elevate it. What’s your process for choosing music?

There’s no real process. Nothing with me is well calculated, smartly thought out and efficient.

There’s good music that you like listening to, and then there’s good music that’s rare, where it feels like you discovered it. Where you think, “Damn, this is so sick. I bet most people haven’t heard this.” That’s rare.

Obviously, I like eerie, creepy stuff. But there’s still haunting stuff that could be lighthearted and very positive. It’s not just not dark. Then there’s this feeling where it stays in your soul. That’s the kind of song where you just know it when it comes past. But it rarely arrives when you’re looking for it.

In my view, there’s a difference between good music — music you like — and music that works well in a skate video. And that’s a big challenge when working with skaters. It’s different if I’m working on a company video based around those skaters. But when it’s a Static video, it needs to have a certain vibe. A lot of times, I won’t use a song that I really like because, by the time I’ve finished that video, I’m not gonna like that song anymore. As an editor, you murder that song.

Skaters will have a song they love, which is difficult because that’s not the point. It’s about picking a song that showcases the skater in the right way in the context of the video. Does it leave the audience thinking about it? That’s the biggest challenge of our time. People remembering what you create and wanting to see it again. Or at least leaving a lasting impression.

That’s really difficult in 2023.

One of the songs in the new video came from seeing a documentary about a certain band. I thought I’d heard all their music. In the documentary, they’re going through their back catalogue, and one of their songs pops up in a movie theatre. I had been killing myself trying to find a song for Trevor Thompson. And from the second that song popped up, all I could think about was getting home and putting his footage to that music.

I got home, whipped up an edit, and it just worked. This happened after already trying 20 songs. I sent it to him. And he was like, “That’s it.”

It’s one of those moments that doesn’t happen in the making of most videos.

Jordan Trahan, backside ollie, Philadelphia.

You obviously think a lot about how you curate the music experience for Static. How do you curate the skateboarders?

It’s very similar to what I was saying about music. Some skaters are good. And there are skaters that give you a feeling. It’s something ethereal. It’s tough because that’s very rare. I couldn’t stack or fill every Static video with a skater that gives me that feeling. I always use the word ‘magic’. I think the most universally agreed upon term is ‘style’.

And it’s not just style. There’s something about the skater’s personality as well, like with Brian Powderly. I hadn’t met him yet. But just seeing the weird way he holds himself. The way he skates. It gave me that feeling.

Jake Rupp was the first example of that for a Static video. I’m from Tampa, and I saw him skating at Tampa Am. I didn’t know him, but I thought, “There’s something about the way that he holds himself. The way he moves.” I don’t even know what it is. But I could just tell that I’m going to be stoked on his personality. I could tell without meeting him and also through his skating.

There’s just something special about certain people. They radiate this kind of aura. It’s so hard to explain. It’s like asking why you like the taste of this particular food – because it’s good.

You’ve documented a lot of skateboarding. Is it even possible for you to pick a favourite video part?

That’s pretty impossible. It’s more [about] the feeling that an overall project gives me. Like Alien Workshop — “Memory Screen” and Stereo — “A Visual Sound”. Those are probably the two videos that give me that feeling the most. They’re so heavily stylised, which a lot of people don’t like. To me, it’s just the feeling I get from how beautifully those were done.

Then there were the characters. Like in ‘New World Order’. I watched Daewon Song’s part six million times. The music is so sick. It’s the videos that capture an era. “Memory Screen” captures an era really well. That was my brother’s generation, where guys were still wearing cut-off pants and frayed shorts with Half-Cabs or (Airwalk) Enigmas.

Everybody in that scene — Scott Conklin and Dwayne Pitre — was like five years older than me, but it captures that era so well. The art direction that Mike Hill put behind that is still the most powerful thing ever made in skateboarding. It’s so fucking brilliant.

Trevor Thompson, switch crooked grind, Armoury, NY.

What changes have you seen in skateboarding over the last 30 years?

There’s a certain way of utilising the street that was the opposite of what mainstream skating was at the time we did the first video. I associate it with the East Coast (USA) because it’s people like (Bobby) Puleo and Quim (Cardona) and Ricky Oyola.

I’ve been saying this in the intros at the premieres. I’m not saying that I or Static are responsible for this. But when the first Static video came out, the big motivation to make the video was that the type of skating we were trying to showcase was not what you saw in mainstream skateboarding, especially not in magazines. And magazines were super important back then.

It probably happened about 12 years ago. Mainstream skateboarding finally caught on to the fact that when you’re driving to the spot, you’re passing all this other stuff that’s so much more interesting. Stuff people can skate more creatively. And you can make a far more interesting skate video by focusing on that.

I’ve been trying to say that without saying, “Oh, we’re responsible for it.” But I’ve been trying to point it out because everybody’s on that same tip now. It’s normal now. And yet, in my opinion, it’s gone way too far.

It’s like a Rube Goldberg machine. That’s what I compare modern skating to now. It’s like one of those cartoons where you roll the egg down the ramp and knock over the domino that knocks the marble down the tube. Crooked grind a handrail, land in some grass, wally a tree stump, and clear a gap to darkslide.

Okay, man, all right. You won. You won skating. It’s amazing. That’s the thing. Wow, that was amazing. But I’m not feeling anything. Why am I not feeling something? This is bumming me out because these guys are killing it.

From my point of view, it became more important to show the personality of the person behind the skating. I don’t want to offend people or come across like a dick, but I don’t want to like everything. Nobody wants to like every sports team. You don’t go to watch a game so that you can root for both teams.

You want to have a certain niche or a group of skaters you’re a fan of, like a (Brian) Powderly or a Jordan Trahan, where there’s an indescribable thing. Maybe lots of people won’t get it. But for other people, you don’t even have to say it to them. They’re like, “Oh, yeah, Jordan’s got it.”

It’s whatever Jake Johnson had. I’m not saying it’s the same. Like, “Oh, they’re the same guy.” But there’s this quality that captures your imagination.

There’s some sort of mystery and magic.

Brett Weinstein, standpipe frontside lipslide, Chicago.

There will be a bunch of younger skaters coming to the premiere. What should they expect?

This was the hardest video for me to make because of the weight of wrapping this up.

There are blatant nods to the old series — nods to specific parts. Over time, I developed a recipe for Static — there are always some new faces. But that’s tough nowadays. With Instagram, everything’s immediate, so all the faces are pretty familiar at this point. Well, maybe not to the rest of the world.

For them, I want to introduce some faces and styles that they’re not familiar with. Then, it’s critical to nod to a couple of characters who laid the foundation of the style of skating that Static is meant to celebrate.

There will be an aesthetic to the video, and there will be some young or new faces you’ve never seen. Then, I’ve peppered in some anchors to the history of street skating and style. That becomes more and more difficult as time goes by. Figuring out the guys who would fit well and who are still skating. Then, there are some surprises tied to the older videos.

It’s like watching your first “Curb Your Enthusiasm” episode in Season Eight. There’s going to be a lot of self-referencing. If you’ve never seen a Static video, you won’t know why it’s in there. But it won’t even affect your experience.

I also wanted to throw a bone to people who’ve been watching the series for 25 years. And I wanted to throw an homage to all the most important video makers who influenced me.

Jordan Trahan, wallride five-0, Long Island. Photo by Pep Kim.

We’ve managed to get the NZ premiere in a cinema. It wasn’t a deal-breaker for you, but it seemed important. Why is that?

It’s the biggest compliment for any filmmaker — I hate to use the word ‘filmmaker’ for skate videos — but when someone works on something for this long, you want people to walk away feeling something.

I want people to have a taste in their mouth that doesn’t go away. It’s the biggest challenge of any media in this day and age — to leave people feeling something. A unique feeling that they can only have through watching your project.

And the best way to achieve that is to surround people with the experience in a theatre. Where they can’t be distracted by their phones. Hopefully, they’re not going to talk to each other.

We did a premiere that was in a bar, and it kills me because I listen to people talking or I see people distracting each other. And I’m like, “God, they just missed that. That’s so important!”

I don’t want to be distracted when I see a skate video, knowing it’s going to be something powerful. If Dan Magee put out a (Blueprint) video back in the day, I’m watching it undistracted. Nobody can talk to me. I want the full experience.

Because you’re never going to have that experience again, all the surprises will have been ruined, and you’re not gonna be able to experience that if you’re texting and your friends are talking to you.

So, in a theatre, you feel it. It’s the best opportunity for somebody to really feel the intention and see the work, the world, and these skaters through my eyes in the way that I want them to see it.

It’s this super rare experience that almost no skaters get any more. To experience something together. To create an energy together because we’re all so separated, watching shit on our phones now. It helps create a community experience.

I remember the few skate video premieres I went to, and I don’t remember how many full-length videos have come out online in the past six months. I could maybe tell you a couple of things about them.

I think the theatre experience is the best way for a filmmaker or skate video maker to feel like their work truly has the best chance to be absorbed, appreciated and understood. The skater’s video parts are going to live on far longer in the minds of the audience if they can see it through that experience.

Christian Maalouf, ollie, St Louis.

To wrap up, Josh, what wisdom can you impart to other filmmakers documenting skateboarding?

Make it memorable and make sure it lasts in people’s memories. Give them a unique experience. That’s the key.

When I was younger, I was trying to recreate the skate videos that I was watching. There’s a recipe, a formula that you see, because we’re constantly inundated with all this media. So, you’re trying to make what you think a skate video is supposed to be.

And I’m a victim of doing it to myself. Recreating the recipe or the thing you’ve done in the past that worked. But the videos that hit me the hardest and most influenced me were where somebody stuck to their vision and offered what was unique to their experience.

It’s so hard not to follow what you think is the way that things are supposed to be done. I’ve done a couple of film workshops for Cons (Converse) with young skaters. And the point I’m always making is not to see how crazy you can make it or shoot the weirdest angle. You need to communicate your unique experience or that of your scene, crew, or city. Then really play on that.

There’s so much content out there. You’re not going to make a difference, and your video is not going to be that memorable if you’re just trying to show, “Oh, my friends are good, and I’m a good filmer”.

We had the benefit of the late 80s and early 90s. All those videos are filled with music made by friends of the skaters. All those H-Street videos, you couldn’t find that stuff anywhere.

I remember I had this list in my wallet, and ‘Operation Ivy’ was the first band that actually popped up in a record store. I went to this indoor skating rink in Florida. I showed up and ran to the DJ booth because I thought I was the first one to get the tape. And I was like, “Dude, if you play this, everybody in here is gonna be so stoked!” I was 14 then — but it was that memorable experience of hearing music for the first time in a skate video.

If I used some new trap song that everybody’s listening to right now, you’re bringing people’s existing associations along with that. If you give the audience an experience they’ve never had, it’s going to last, and when they hear that song that they had never heard before, they’re always going to think of your video or your art.

You want to make something that people respect. You’re comparing yourself to other things and doing what you think you’re supposed to do. But if you can step out of it and come up with a way to give people your unique point of view, it will make it much more meaningful.

If people feel like what they’re watching is really meaningful to you, it will mean more to them. And if you treat it with respect, it will influence other people to respect it.

Respected video makers are making videos that take them two years. A couple of big websites will host one or two of the parts. And three days later, a full-length video comes online. Then everybody forgets the thing that came out two days ago. It’s like it doesn’t exist.

You have to come up with ways to respect the project and for other people to respect it. You need to figure out ways to provide people with a unique experience.

That’s the biggest challenge.

Josh Stewart, filming in NYC. Photo by Cole Giordano.

Get your FREE ticket for the NZ Premiere of Static VI in Wellington.

When Chris Jackson is not making his ten-yearly contribution to Manual, he can be found skating curbs or keeping himself busy creating futures and helping designers create successful teams, cultures and careers.