That it’s not possible for the image to be viewed only in an objective manner, or judged purely on set criteria, themselves making the image good or bad.

Fashion photography, by way of example, is purely subjective. It has no rules to adhere to, no criteria that must be met and, in some instances, can break even the most basic tenets of photography and still be considered worthwhile, good or even groundbreaking.

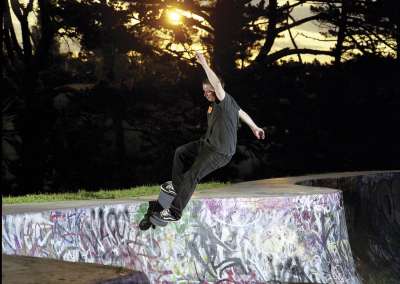

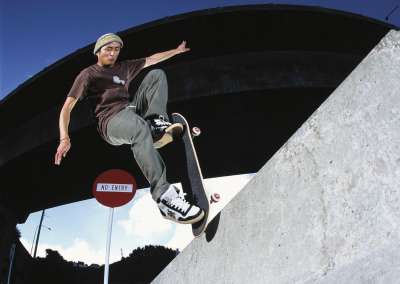

By contrast, skateboard photography, paradoxically, can be viewed subjectively but also by an objective set of rules. The viewer can hold an opinion on the content of the photo, the trick, the skater, the location, the difficulty, any number of subjective reasons, but should it fail any of the objective criteria, it’s destined for the figurative trashcan.

These objective criteria move forward with the times, new possibilities opened up by the advance of technology. Of these, the most important are exposure, image sharpness, and composition. Without these, the image runs the knife edge of what is good and bad.

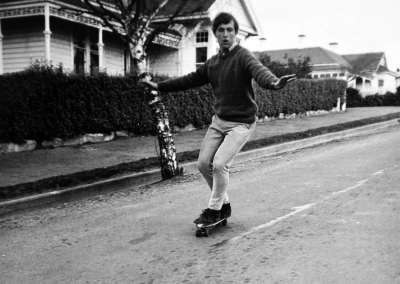

Contemporary digital skate photography has reached its current apex of image quality on the back of advances in resolution, sensor size, and the advent of high speed sync flash. Where this generation of skate photographer triumphs, previous generations struggled with the limits of analogue technology, film, and flash.

The fluid nature and beauty of these objective criteria mean that even a film shot from the 90s can still be regarded as good when viewed in this context.

The difficulty facing print magazine editors in today’s world of daytime flash, super-duper fisheye and spot-on exposures, is to look past the objective, and again focus on the subjective, because once the objective is achieved, the viewer is again allowed the freedom to like or dislike based purely on the length of the skater’s pants.